Our Philosophy of Art and Training

"The abstract finer sensitivities of judgment, feeling, ennobling thoughts and appreciations create the abstruse, unseen quality that defines art. A pictorial representation is always a translation. Nature suggests ideas for interpretation, the artist supplies ideas of how the interpretation is to be made." — Edgar Payne, landscape painter and author of Composition of Outdoor Painting.

Important Differences Distinguish Today's Programs

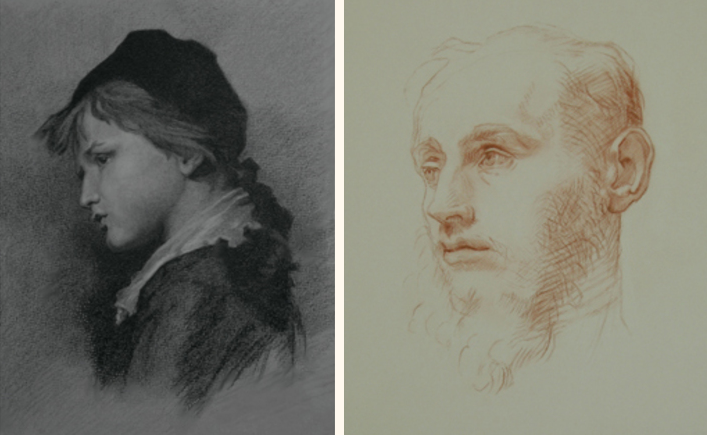

As with the majority of realist academies sprouting up around the globe, the AAC emphasizes the teaching of fundamentals — focusing primarily on drawing. However, elementary aspects of color and paint are introduced relatively early at our atelier, with some core philosophical and practical ideas differentiating our program from many others.

Choosing where to secure a strong foundation in drawing and painting instruction is an important decision. This should be based on a careful preliminary analysis of the programs and how they are defined. The challenge for the would-be student is that a fair amount of study of art from the past is often required before an understanding of the differences between various programs can be appreciated.

"The art of representational painting is founded on the organized interplay of abstract patterns with finely rendered aspects of visual truth, and the merit of pictures should be judged primarily on that basis." — R.H. Ives Gammell, representational artist, instructor and author.

Following a century of modern "abstractionism," a reaction has catapulted us to the opposite end of the artistic scale. Rather than works that are "abstractly expressive" and lack pictorial "realism," we now have realistic works that often lack sufficient pictorial expression. Is it not an appropriate time to acknowledge that most of us who are interested in representational art truthfully respond to work that embraces both an intelligent analysis of nature and imaginative inspiration?

Traditional Poetic Realism Is Not Literal Realism

Regardless of how "realistic" you wish your art to appear, art doesn't just happen after learning how to competently render form. One also has to learn a good deal about art. It's not just a matter of plotting points, learning to see values and making highly finished drawings; it reaches deeper than that. Many teachers today suggest studying the masters but don't really teach you how to go about this effectively. In addition to the considerable effort involved in learning to observe accurately, learning how to artistically translate the natural world represents an equally formidable challenge, and it is this important area that is all too easily compromised or neglected in schools teaching realist skills.

Traditionally, drawing and painting have more in common with dance and music than with photography. The interpretive, expressive components shared with these sister art forms play a very important part in the art of representation. If this idea is not fully appreciated and the language of visual expression is not sufficiently introduced, an artistic deficiency will hamper students' ability to cultivate qualities in their work that are a major part of the works they wish to emulate.

At the AAC it is felt that much of today's realist art is, by traditional standards, much too literal, often evincing a dry, uncanny quality reminiscent of plastic fruit or wax figures, and appearing at times, perhaps ironically, somewhat unreal. It is the artist's emotional response combined with his or her intellectual analysis that has the potential to convey a lasting and universally meaningful visual reality. This artistic translation deals with the subject's nature in a way that resonates poetically and convincingly, as opposed to simply impressing the viewer with its conveyance of sameness. What seems to be lacking today is sufficient appreciation of the formal interpretive elements in fine drawing and painting that transcend the limitations of straightforward replication. These elements are derived from an in-depth conceptual and technical exploration of the masters — those aspects embedded in the entertaining refinement of a Fantin-Latour, the spirited naturalism of a Velazquez or a windy Corot, all realistic in name yet undeniably more poetic in essence.

By learning the nuts and bolts of the varied traditional approaches, students take on those influences that inspire and edify them. Their perception of the natural world is closely entwined with careful analysis and cultivated appreciation of fine works of art. Taking a more interpretive approach to representation does not mean that one cannot develop a high degree of natural appearance in one's work. In fact, it often means quite the opposite. It simply depends on one's governing concept of beauty and truth. When Leonardo da Vinci spoke of the keen observation of nature, he was intimating that there is more to seeing than is involved in the literal copying of shapes and tones. The renowned Robert Beverly Hale illustrates this concept beautifully in his books on master figure drawing and artistic anatomy. He writes that the student must learn to conceive what is being perceived, and that while learning to render form convincingly the student must learn to interpret it artistically, deciding for him- or herself what to put in and what to leave out, what to play up and what to play down — how to artistically "re-present" things. Today it is evident that there is far too much habitual piecemeal "seeing and putting in" at the expense of genuine artistic selection, orchestration and summation.

Avoiding an Over Reliance on Literal Training

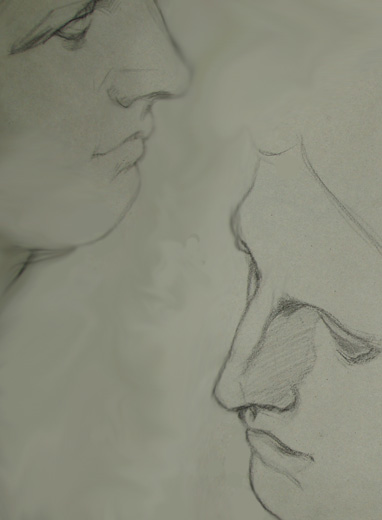

"In representational painting, what is on the canvas is always a metaphor for reality. You're not really painting a nose, you're making a collection of visual signals that say 'nose' to the viewer." — Gregg Kreutz, artist and author.

In the end, work from nature and the artist's own ideas will not mesh well with the mindset of students who have been over-focusing on literally duplicating what they see in front of them. With perception blanketed by the belief that it is important and possible to see everything "very accurately, just as it is," the conceptually disengaged student will be forced to repeat the doleful steps of manufacturing such imagery always in the same way. The student will never have learned to give much thought to his or her feelings about the subject or, more importantly, how to convey them using a visual language of representation.

Would-be students' difficulty in appreciating the risk of becoming too literal-minded is all too often reinforced by those around them who applaud the results of their early efforts. A public all too familiar with the appearances of photography, and much less acquainted with the appreciation of the traditional purpose and meaning of art, will often praise such work, referring to how "realistic" or "photographic" it appears, and how "clearly demonstrative" it is of "academic," "traditional" or "classical" training. It is not surprising that whereas in the last century we had a type of art-appreciation amnesia clouded by 20th century "isms," we now have a rise in appreciation limited to the straightforward replication of visual fact(s). This inventory-taking approach to picture-making is predestined to miss out on the inspirational spirit that more rewardingly translates the visual "facts" into a meaningful work of art. This is what the great French draughtsman Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres referred to as "the distortion of nature on her own terms."

The current trend toward non-traditional literalism is likely related, in considerable part, to the heavy reliance on the sight-size method of training employed by many of today's academies. Briefly, the sight-size method is a way of working that establishes same-size comparison between work surface and model. Like training wheels on a bicycle, it can be useful in helping beginners who are trying to learn to see more accurately. However, if it is relied upon too much, it tends to foster a rigid dependence on depicting visual information in a very fixed manner (exactly what is not required in order to represent things along more traditional lines) and impede the development of the artistic judgment and fluidity of execution so important in the creation of art, yet surprisingly today so undervalued. (For more detailed information regarding the pros and cons of the sight-size method, please see our page Concerns About the Sight-Size Method and Artistic Development.

In a school setting, the repetition of sight-size studies can also consume time and attention that might be allocated to learning other aspects of the language. Training that is heavily weighted toward sight-size instruction can easily lead to inexpressive picture-making. (The figure and landscape are two genres in which an overly literal mindset will really find itself working against the grain of conveying a sense of life in the subject). Breaking free from too fixed an approach without developing good artistic decision-making skills can be very difficult, and a study method that ultimately overemphasizes the exact matching of subject and representation should be carefully limited. The positive things to be gained from sight-size can nearly always be acquired by the student within the first few exercises using the method, making any further number of similar undertakings redundant. With the essential lessons attained, sight-size should be considered to have served its purpose and the "training wheels" be removed. Reinforcement or perfection of these skills can be achieved after switching over to the comparative method, without the downside risk of its becoming too habit forming. The comparative method allows for the application of greater artistic judgment, important in making things appear not only real but also artistically vibrant, alive and evocative.

Learning to Translate Nature: The Great Assignment of Art

"That nature is always right is an assertion artistically as untrue as it is one whose truth is universally taken for granted. Nature is very rarely right, to such an extent even that it might almost be said that Nature is usually wrong; that is to say, the condition of things that shall bring about the perfection of harmony worthy of a picture is rare and not common at all." — James Abbott McNeill Whistler, artist/painter of Whistler's Mother.

While the notion that nature is not art is generally accepted, recognition that the copying of it is also not art is less understood. A dialogue that more specifically fleshes out what the differences are between nature, copying nature and artistically translating it is largely missing. Traditional artists have always considered interpretation and the capacity for artistic manipulation in tandem with their examination and representation of nature. In order to create inspiring pictures of the highest order, one learns equally from fine works of art and the careful observation of nature. This is learning in the true Renaissance spirit.

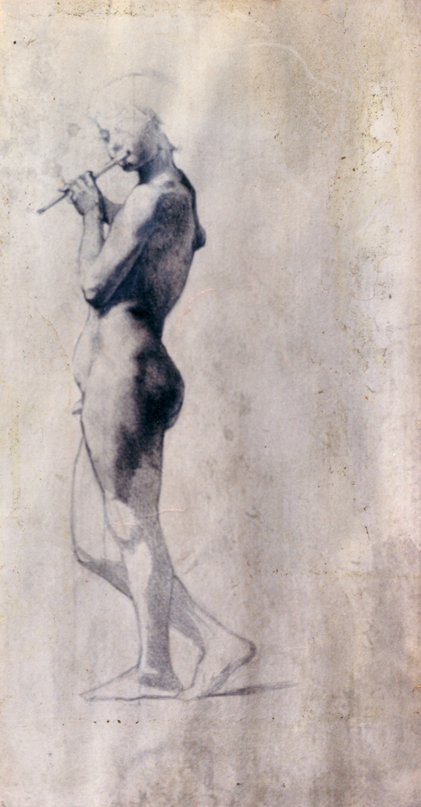

The masters used the tools of expression to draw and paint up to their inspired idea of the subject, not to produce a literal copy of a fixed set of points from a stationary model. The great masters' exploration and interpretation of nature resulted in decisions about composition, color harmonies, rhythm, gesture, technique, artistic proportion and style, etc. that we feel as beautiful or uplifting. Analysis of their work often reveals as much concern for motion as for the rendering of form. It is only with an understanding of these concepts that the painter can develop a more evocative presence and charge the subject with a poetic spark, creating painting of the highest order. Artists who interpretively manipulated literal reality are Leonardo da Vinci, Caravaggio, Correggio, Titian, Rembrandt, Rubens, Sargent, Leighton, Waterhouse, Degas, Courbet, Gentileschi, Hunt, Bouguereau, Whistler and Annigoni (by no means an exhaustive list). These aspects are central and should be carefully studied alongside the development of more mechanical aspects related to the rendering of form.

An example of this kind of artistic conceptualization at work is found in the French draughtsman Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres. To make the neck of the model in his drawing appear to be the size it actually is in life — and to make it more beautifully true to art — he considers whether to make it narrower or wider than its actual measured size. Many great artists such as Raphael, Velazquez, Delacroix, Degas, Vermeer and Rembrandt consciously worked in this conceptual way.

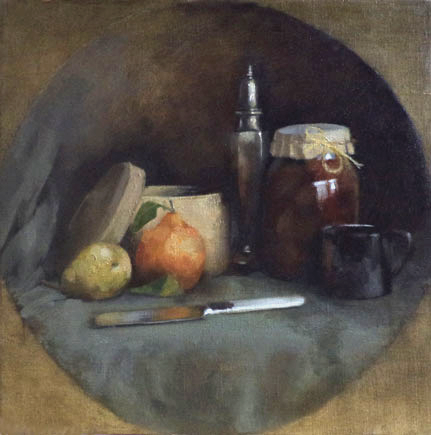

Another example: Suppose we are painting a bowl of fruit and wish to convey the idea of warmth in our painting. The use of an enduring color harmony based on the idea of warmth would prove more appropriate for conveying that which we sense or feel about our subject rather than the literal matching of individual color swatches taken straightforwardly from the individual pieces of fruit. The "perfect and actual" color match of the single apple in question would therefore be more aptly subjugated, within the realm of believability, to our overall color strategy. Alternatively, to convey a sense of intense vibrancy, we might select a different color strategy. The point is that in both cases we would be consciously trying to convey something of an interpretive idea or feeling in response to the subject, within the realm of believable color, beyond the mere reporting of the subject's actual hue. We would be consciously setting up an appropriate, interpretive system, working not from the model, but rather with the model. Such a result might not satisfy some as "real" — that is, similar to a photograph or everyday factual reality, if one is taking as one's starting point photography or everyday factual reality. However, for those whose artistic vision has been cultivated by the finest examples of traditional still life, such results would indeed pleasantly appear less photographically or factually real — but certainly more artistically real, more beautiful and truthful to the big ideas of nature and great art. The question quickly becomes one of just what does govern perception, and the answer, in turn, is based on the extent to which one values a poetic notion versus a literal one.

From a traditional standpoint, the intellectual and emotional interpretation of nature becomes the artist's greatest challenge, a full commitment to the imposition of expressive order conforming to nature's bigger truths. Enslavement to the mere copying of nature's incidental effects falls short of the assignment of making art — no matter how much skilled rendering technique cosmetically adorns the empty result. Fine drawing and painting demands much more from the artist in the name of visual play, pictorial unity and aesthetic refinement.

The AAC Offers a Balanced Approach to the Study of Art: Realism and Artistry

"The so-called 'secrets of the masters' then, all boil down to the lifelong challenge of learning how to observe and understand our feelings about nature." — R.B. Hayle, figurative artist, instructor and author.

In addition to teaching the technical accuracy of the sight-size and comparative methods of proportion, study time is also allocated to learning about the technical and conceptual artistry of past schools of painting.

Today's schools must clear the way for students' understanding that they will always be offering the viewer an artistic concept of what it is they see as artists, and that this offering includes a big part of themselves (without drawing self-conscious attention to this). These shared inspirations (more commonly referred to as pictures) are most effective in conveying original ideas when the artists are interpreting and orchestrating those bits of factual reality that serve their artistic purpose. Instead of enslaving students to subjects that can only be positioned directly in front of them, the Academy of Art Canada is dedicated not only to the development of the elementary skills of early students, but also to the important training that will liberate them from the limitations inherent in these methods — guiding the mechanical practice, at the earliest possible time, into a more fluid, organic execution, a stronger artistic judgment and a greater sense of poetic resonance and artistic unity.

The AAC is committed to offering knowledgeable instruction and a comprehensive program in a warm and friendly learning environment for the sincere, discerning student who wants to learn more about the art of traditional representational drawing and painting.